Soccer: Keeping your goalkeepers active

So heres how it goes: “All right, everybody out on the field,” says the coach — and then he sees the goalies. “Oh, you two, go over there and do whatever it is goalkeepers do.”

In far too many programs, that’s about how much coaching the goalies get. And it’s a mistake.A superior goalie is worth two or three games a season,” said Ron Chell, the goalie coach at Notre Dame de Namur University in Northern California, where in 2011 Isiah Castro was second in the nation in Division II, allowing just 0.47 goals a game.

Not surprisingly, the Argos finished 13-3-2, and Chell felt though they might only get stronger. Based on his background, he should know. A native of the Midlands in England, and steeped in that country’s soccer tradition, he has been in the United States for 10 years, mostly coaching goalkeepers.

And unlike many keeper coaches, who work on diving and making the spectacular save, Chell focuses on the mental aspect of a very demanding position. “At the high school and collegiate level,” he said, “keepers need to be loved. Goalkeepers are delicate flowers — they are always the people who get blamed.”

Like closers in baseball, goalies must have short memories. “You have to get over it,” says Chell. “Even if you have a stinker of a game, you have to try to laugh it off.”

Chell also emphasizes that the best save is the one that doesn’t involve the keeper. “You don’t have to touch the ball to make the save,” he says, and that means communicating with the defenders. “Don’t ask, tell,” Chell reminds his keepers, and of course, they have to understand the game to tell their teammates the right thing.

“Goalies are the most analytical players on the field,” he says. “They must have the ability to understand tactical situations, and then they have to communicate that understanding to their teammates.”

And it wont happen overnight. “I had a dad come to me for some private coaching for his 10-year-old daughter and he said, ‘This will take about 12 weeks, right?'” Chell could only laugh. “If you stick with this position, you’ll still be learning when you’re 40.”

Here are three ways Chell works his keepers in practice.

5-on-5

In this drill, there are five attackers, five defenders and a goalie. The coach stands 25 yards in back of the penalty box, behind the attackers, who are 10 yards in front.

DIAGRAM 1: 5-on-5. Each defensive player has a number, as does each offensive player, but the offensive players must start at a designated flat cone. When the coach calls out a number, he or she simultaneously kicks a ball just outside the penalty box. The offensive player with that number tracks down the ball and the corresponding defensive player moves out to challenge, but does so passively, so that the attacker can deliver a crossing pass into the box.

DIAGRAM 1: 5-on-5. Each defensive player has a number, as does each offensive player, but the offensive players must start at a designated flat cone. When the coach calls out a number, he or she simultaneously kicks a ball just outside the penalty box. The offensive player with that number tracks down the ball and the corresponding defensive player moves out to challenge, but does so passively, so that the attacker can deliver a crossing pass into the box.

Once the offensive sequence is finished, either with a goal or with a clearance, the attackers sprint back to their designated flat cones, the coach calls out another number and kicks another ball to the side of the penalty box. Players must get used to hustling back to their positions quickly, which helps the overall transition game.

An assistant coach should be stationed near the goal to talk to the goalie about each play. Ideally, there are two keepers, so the assistant can talk to one about the previous situation while the next goalkeeper is handling the next attack.

The key is to have constant attacks, and, of course, coaches can ask the offensive players to try to pinpoint specific areas: near post, far post, etc.

Done well, this drill involves attackers (who not only must work on their crosses but also must make good runs at the goal), defenders (who can be rewarded for outlet passes to specific areas of the field) and, of course, keepers.

One nice variation is to put the attackers on defense, and the defenders on the attack, which makes sense in modern soccer given the versatility demanded of todays players.

Foot skills

Goalies must do more than just catch the ball — they also have to handle it with their feet, and this basic drill makes a difference.

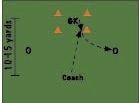

DIAGRAM 2: Foot skills. The coach stands 10 to 15 yards away from the keeper, who is in a box outlined by four cones one yard apart. The coach passes the ball to the keeper inside the cones, who must control it, and then kick it back to the coach.

Goalies should work on stopping the ball with the inside right foot, then passing both outside and inside, then do the same with the left foot. Adding another player at a 45-degree angle on each wing gives more of a game feel to the drill, as that is usually where the outlet pass goes.

Dive & recover

Keeping goalies aggressive is important, as is working on their ability to recover quickly. This drill does both.

DIAGRAM 3: Dive & recover. There are three tall cones set at one side of the goal mouth at five-yard intervals. There are three flat cones lined up in the middle of the first three at 7.5 yards, 12.5 yards and 17.5 yards. The coach is 25 to 30 yards from the goal with a pile of balls.

The drill begins with the goalie shuffling to the post, then back to the center of the goal. The goalie then uses fast-feet-sideways movement to the first tall cone and knocks it over with his or her hand. The goalie then moves toward the first flat cone and the coach shoots in that direction. The goalie dives for the ball, recovers as quickly as possible, then uses fast feet to slide over to knock over the next tall cone. At that point, the goalie heads back to the middle, the coach shoots again and theres another dive and recover.

By the end of the drill, the keeper is nearly 20 yards from the goal and is combining an aggressive approach to stopping attacks with a drill that emphasizes agility and quickness.

Do this drill on both sides and ideally more than one goalie is involved to maximize effort. Each keeper should go through the drill three times.