Basketball: Principles for attacking zone defenses

The zone defense remains the scourge of our basketball coaches. Many of them simply rely on superior talent to break all the zone defenses they face.

Other coaches use (1) complicated offenses with “rocket-science” theories, (2) the zone defense as if it were just an old dragon waiting to be slain with an intricate set play, or (3) check to see how some “hot” coach is handling the zone problem.We believe you fail your players by not teaching them how to think the game in such needy areas. Players no longer have the patience to test or probe the zone defense to see how the defense will respond to a given action with a specific tactic or rotation.

After years of working at 11 basketball camps, I took a few summers off from the sweating, sore feet, strained voice and teaching. Inevitably, I chose to do a few camps during the summer.

It quickly became apparent that the players had to be taught the basic principles used in attacking the zone and the reasoning behind each principle. They also had to be explicitly told what each of their individual strengths and weaknesses were. This is not to say that you should make robots of them — having certain players never shoot, only pass.

What the players have to learn is to never attempt to make a play that is not there, has no purpose or they are incapable of making at this point in their development.

As individual players demonstrate improved skill levels in practice, along with better judgment and decision-making, they should be encouraged to do more, not less.

Here are some of my particular favorite “don’ts” for inclusion in your overall approach to teaching zone offensive tactics and principles.

- Don’t catch and immediately dribble.

- Don’t make a pass to the place you were told to pass (in practice) even though it is not open.

- Don’t take a 3-point shot without a penetrating pass/dribble to collapse the zone.

- Don’t take a quick shot early (except for a layup) in the possession (“But Coach, I was wide-open!”). There was a good reason why you were left open!

Unnecessary dribbling, forced passes and rushed shots are all things that must be eliminated from every player’s mentality.

During a camp session, I was teaching “attacking zone” principles to the players in grades seven through 12 when my thinking became crystallized: Internal progression and methods for reading, analyzing and attacking zones had to be straightforward and direct.

I began using the zone attack principles during station work: The principles for beating the zone are as simple and understandable as can be. They are in order of importance:

- Spacing

- Player movement

- Penetration

- Ball reversal

- Weak-side attack

- High-low (& low-high)

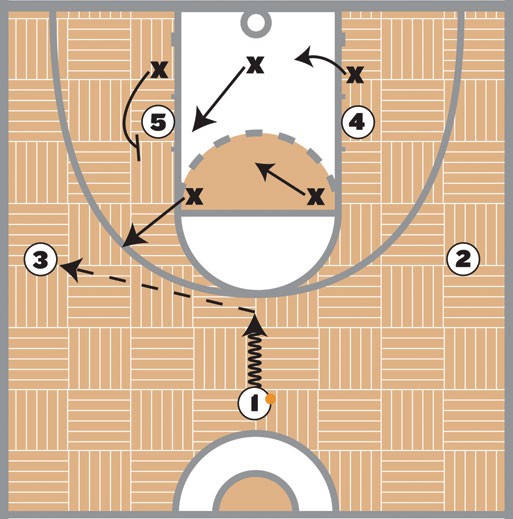

It became clear that spacing should be the one idea every player, regardless of age or experience, should take away from the teaching station. More specifically, if spacing is principle No 1, gap-spacing is No. 1A and of paramount importance when facing zones (Diag. 1).

|

| Diag. 1, Gap Spacing: Example of a 3-2 offensive set that puts the players into the gaps of the 3-2 zone defense. |

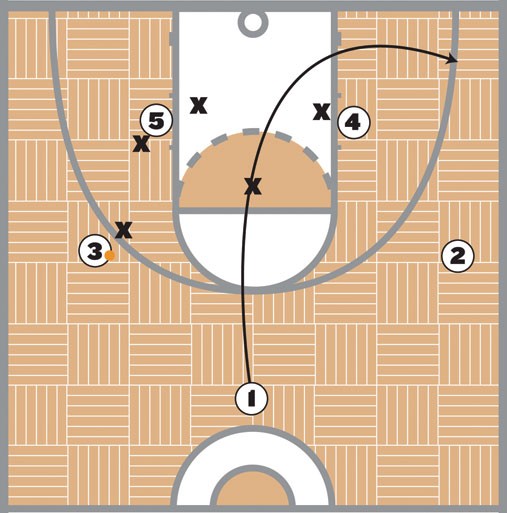

With players spaced in the gaps (approximately 15 to 18 feet apart) and available for passes, principle No. 2 (player movement) becomes critical (Diag. 2).

|

| Diag. 2, Player Movement: Basic player movement after the wing entry. Note that the zone focuses on the wing and ball-side post, ignoring the weak-side cut and subsequent slide to the high elbow. |

Regardless of the way that they move, with a cut or slide along the perimeter/in the lane, or they screen or a seal in/near the lane, players have to space themselves in gap areas (away from zone defenders) whenever possible.

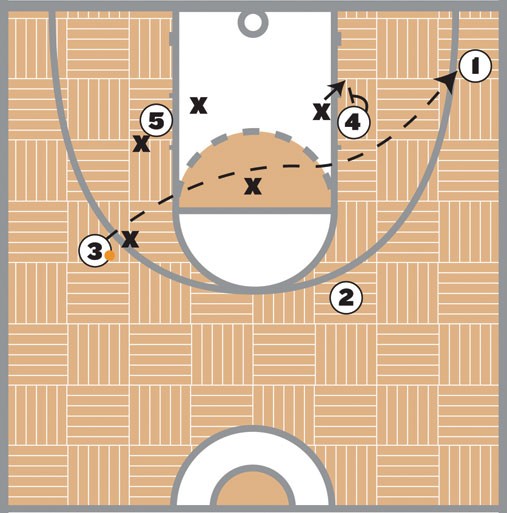

Next, because of the spacing and gap-spacing, zone defenses begin to stretch out-of-shape to cover the ball-side offensive players, leaving open weak-side areas for offensive players to fill. When that happens, players should look to utilize principle No. 3: Penetration (Diag. 3). In this case, penetration of the gaps, seams and other openings in a zone can most simply be accomplished via the pass to open or “filling” players.

|

| Diag. 3, Penetration: Defense has responded to the ball by overloading or over-committing. 3 does not force the post pass; he skip-passes over the zone to 1 at the arc-block. 4 seals the baseline defender to facilitate a pass. |

As seen with even the youngest players during live 5-on-5 action at the station, once the players grasp the principles of spacing, movement and penetration, they begin to make life difficult for the defense.

After utilizing the first three zone principles, players were ready for the first zone concept: Identifying defensive/offensive advantage. Having players stop (on the whistle) to observe the zone shift is critical when the ball is on one side. The easiest way to get anyone to see the necessity for the fourth principle, ball reversal (Diag. 3), is to look at the helpline (a.k.a. the mid-/rim line).

Since zones are built on the premise of rotating defenders to the ball early, it’s easy to see zone imbalance (i.e., defensive overload). When facing the most common zone, many teams use a 3-2 or a 1-3-1 offensive alignment.

With a wing entry pass and a simple weak-side cut or slide by the passer, an immediate shift by the zone creates a defensive overload (Diag. 2). Then the whistle blows, freezing all 10 players.

On the stoppage, with the ball at the wing and a forward at the mid-post, there are three-and-a-half defenders from the helpline to the ball covering two offensive players — clearly a defensive advantage.

On the weak-side, there are two perimeters outside the arc and a forward at the mid-post with one-and-a-half defenders from the helpline covering three — clearly an offensive advantage. Observation and simple math will allow anyone ball-side to see the need for quick ball reversal (Diag. 3) by quickly passing around the perimeter or a sharply-thrown skip pass over the top of the zone.

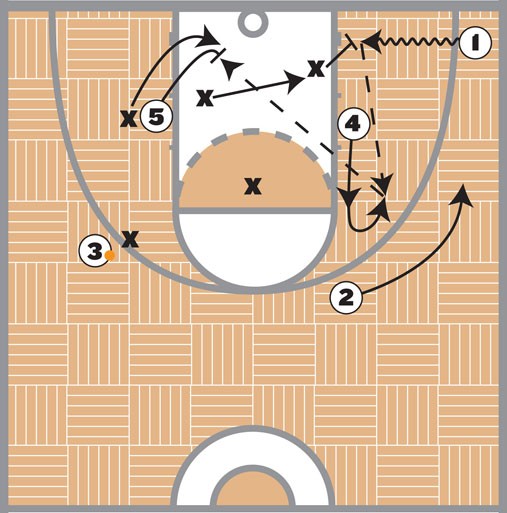

By this time, most of the players realize that the first four principles are good, but not quite good enough. All the variously aged players will, through trial and error, find that the fifth principle — weak-side attack (Dia.4) — adds to the effectiveness of the other zone principles.

|

| Diag. 4, Weakside attack: After taking 3’s skip pass, 1 slashes hard to the block. 4, spotting this, moves quickly up to the elbow, ready to catch the ball and shoot or pass (low-high). He can now shoot, kick-out to 3 or 2, or pass to 5, who has sealed off the near X, then looks for the pass (high-low) from 4. The kick-out to 3 or 2 can set up a 3-point shot. |

They become aware that continued ball reversal stretches the zone sideline-to-sideline, flattening the zone and leaving gaps. This allows the offensive players to attack the weak side by catching in a triple-threat position and feeding the post, slashing to the hoop, shooting (12-15’) jumpers and taking 3s.

Ball reversal, weak-side attack and a flattened/stretched zone combine to open the foul-line area for the sixth principle: high-low/low-high interior attack/post passing (Diag. 4). Utilizing the inherent center gaps in the 2-3 and 3-2 zones can yield high-percentage plays.

Two routinely accepted concepts used against zones are dribble penetration and spreading the floor for 3-pointers. Both are excellent methods to break down zone defenses. However, the reason dribble penetration and 3-pointers were not mentioned prior to this point is very simple. Too few players possess the necessary dribbling and passing skills. Similarly, the reason taking 3-pointers is not mentioned more prominently is because too few players take good 3-point shots. Players with these skills and recognition abilities are often in short supply, but not truly necessary to beat zone defenses.

Players can breakdown defenses after learning zone concepts and understanding how to efficiently use their skills. Once coaches simplify things and establish their own zone concepts and principles, they can develop players and teams that embrace their preferred zone tactics.

By teaching players how to dribble less, pass more, and take high-percentage shots, coaches can develop players who possess a nuanced understanding of how to play, not just players who know plays.